- Artist/Maker:

- Eleanor Antin

- Bio:

- American, b. 1935

- Title:

- Vilna Nights

- Date:

- 1993-97

- Medium:

- Mixed media installation

- Dimensions:

- Dimensions variable

- Credit Line:

- Gift through the Estate of Francis A. Jennings, in memory of his wife Gertrude Feder Jennings, and an anonymous donor

- Accession Number:

- 1997-130

Not On View

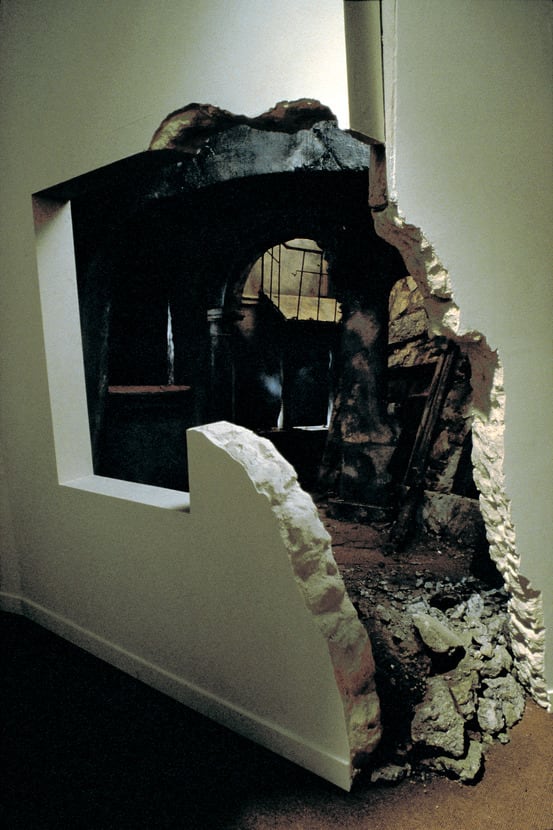

Infused with a deep sense of loss and sadness, Eleanor Antin's Vilna Nights creates an environment of a place and a time that are long lost. Commissioned by The Jewish Museum for the 1993 From the Inside Out: Eight Contemporary Artists exhibition to inaugurate the museum's new exhibition space, the mixed media installation appears as a ruined shell with a bombed-out courtyard. Through a demolished wall, the viewer can peer in on three vignettes of life-size projections onto windows.

Each of the vignettes is a fragment of shtetl life in a private interior. One scene depicts a woman sitting by a furnace and weeping, the fire illuminating her face. She reads from a bundle of letters tied in a ribbon. As she reads each letter, possibly from a dead or lost lover, she becomes increasingly distressed until she throws the letters, one by one, into the furnace to be burned. In another window, the viewer peeks in on an old Jewish tailor working by candlelight at his sewing machine. A sadness pervades the scene as the old man sews articles of clothing and then carefully folds them. This melancholy reaches its height as the tailor finds a yarmulke that prompts him to begin crying, and then the candlelight flickers out. The third scene captures a young boy and girl, presumably brother and sister, appearing cold and hungry as they share a small piece of bread. Magically, a lit menorah appears in midair, and following it chairs and a table set with food and drink. The youngsters are ecstatic as they sit down to enjoy this unexpected meal. However, just as they are about to begin eating, the magical objects disappear, one by one, leaving the children alone and hungry as they first began.

Recalling Antin's 1991 feature-length film The Man Without a World, this mixed media installation allows the viewer a glimpse of a vanished world and life that no longer exist. Vilna, the capital of Lithuania, was the major European center of Jewish culture and learning and home to the largest Eastern Europe Jewish population in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. However, the Holocaust exterminated that Jewish population and life; this fact, while never directly named, suffuses the entire installation. Each of the three filmic vignettes recalls Yiddish cinema and the fantastical qualities of early film and film editing, again underscoring the fact that this genre abruptly stopped thriving at the onset of the Holocaust. The theme of a fire or flame that is extinguished and its association with sorrow in each of the narratives mirror the life and culture in Vilna that were extinguished.

Along with the architecture and images in Vilna Nights, a soundtrack of shtetl life saturates the environment. One can hear the wind howling, a train passing by, a dog barking, and church bells ringing. The sound begins at a low level and increases throughout the soundtrack, adding drama to the scenes in each window. The combination of the architecture, the images, and the ambient noise creates a nearly realistic environment, underscoring that this world is no longer a reality. The installation emphasizes constructed experience of memory, especially the memory of events that one has not personally witnessed, leaving visitors with the sense that they are merely voyeurs into these private, lost, fabricated lives.

Each of the vignettes is a fragment of shtetl life in a private interior. One scene depicts a woman sitting by a furnace and weeping, the fire illuminating her face. She reads from a bundle of letters tied in a ribbon. As she reads each letter, possibly from a dead or lost lover, she becomes increasingly distressed until she throws the letters, one by one, into the furnace to be burned. In another window, the viewer peeks in on an old Jewish tailor working by candlelight at his sewing machine. A sadness pervades the scene as the old man sews articles of clothing and then carefully folds them. This melancholy reaches its height as the tailor finds a yarmulke that prompts him to begin crying, and then the candlelight flickers out. The third scene captures a young boy and girl, presumably brother and sister, appearing cold and hungry as they share a small piece of bread. Magically, a lit menorah appears in midair, and following it chairs and a table set with food and drink. The youngsters are ecstatic as they sit down to enjoy this unexpected meal. However, just as they are about to begin eating, the magical objects disappear, one by one, leaving the children alone and hungry as they first began.

Recalling Antin's 1991 feature-length film The Man Without a World, this mixed media installation allows the viewer a glimpse of a vanished world and life that no longer exist. Vilna, the capital of Lithuania, was the major European center of Jewish culture and learning and home to the largest Eastern Europe Jewish population in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. However, the Holocaust exterminated that Jewish population and life; this fact, while never directly named, suffuses the entire installation. Each of the three filmic vignettes recalls Yiddish cinema and the fantastical qualities of early film and film editing, again underscoring the fact that this genre abruptly stopped thriving at the onset of the Holocaust. The theme of a fire or flame that is extinguished and its association with sorrow in each of the narratives mirror the life and culture in Vilna that were extinguished.

Along with the architecture and images in Vilna Nights, a soundtrack of shtetl life saturates the environment. One can hear the wind howling, a train passing by, a dog barking, and church bells ringing. The sound begins at a low level and increases throughout the soundtrack, adding drama to the scenes in each window. The combination of the architecture, the images, and the ambient noise creates a nearly realistic environment, underscoring that this world is no longer a reality. The installation emphasizes constructed experience of memory, especially the memory of events that one has not personally witnessed, leaving visitors with the sense that they are merely voyeurs into these private, lost, fabricated lives.

Information may change as a result of ongoing research.