- Artist/Maker:

- Alice Neel

- Bio:

- b. 1900, Merion Square, Pennsylvania; d. 1984, Manhattan, New York

- Title:

- Meyer Schapiro

- Date:

- 1983

- Medium:

- Oil on canvas

- Dimensions:

- 42 × 32 1/8 in. (106.7 × 81.7 cm)

- Credit Line:

- Purchase: S. H. and Helen R. Scheuer Family Foundation Fund

- Accession Number:

- 1995-111

- Copyright:

- © Estate of Alice Neel

On View

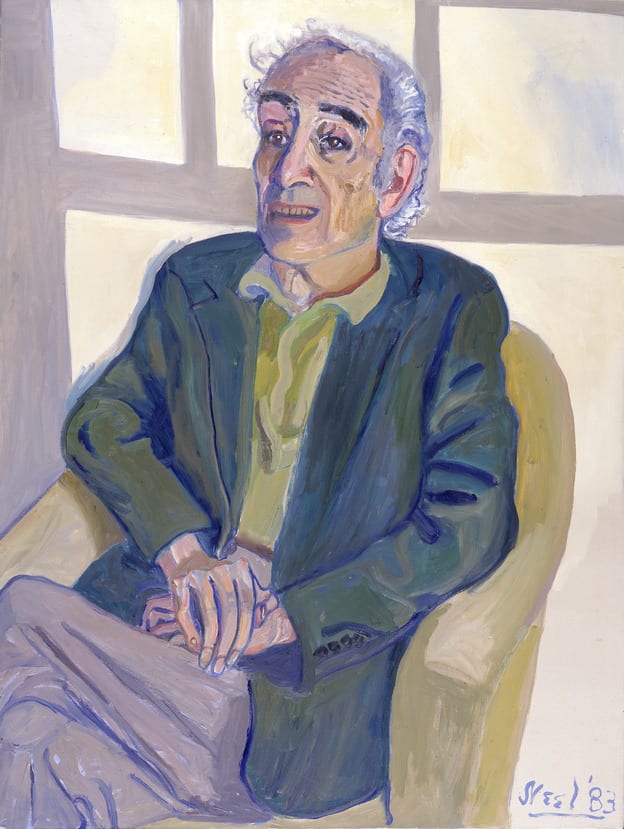

Alice Neel's depiction of the art historian Meyer Schapiro stands at the end of a long line of psychologically penetrating portraits. Born four years before Schapiro, Neel adamantly pursued a career of figurative painting against the dominance of abstraction. By isolating her sitters in the comfortable setting of her studio and applying an expressive use of color, Neel sought to capture the individual characteristics of the public personalities that peopled her bohemia.

In 1983, Neel turned her unflinching eye to a man renowned for his penetrating gaze. Schapiro sits cross-legged with hands folded in his lap, his thin frame filling the armchair. To the pathos of his face Neel adds gray wisps of hair touched with falling light, which suggests a halo of luminescence. His expressive eyes are widened by the raising of his thick brows; the careful delineation of the wrinkles on his forehead proclaims the act of seeing as an act of will. His lips are parted; he is about to speak. The painting is a conversation between an eighty-three-year-old woman and a seventy-nine-year-old man, between two people who had been moved by but had outlived the political ideals of the thirties, between an artist and a critic who, whether looking at a person or a work of art, combined shrewd analysis of the historically conditioned with visionary understanding of the uniquely individual.

Meyer Schapiro was born in Lithuania in 1904 and at the age of three moved to the United States, where he and his family settled in the predominantly Jewish community of Brownsville, Brooklyn. As a professor of art history at Columbia University, Schapiro was mentor to a number of famous artists, historians, and critics. He was a prolific writer, and his boundless interest was variously captured by the ecstatic tensions of a Romanesque portal, Courbet's empathy for the French peasant, the psychological implications of Van Gogh's boots, and Cezanne's apples as sublimated desires. Yet Schapiro never proclaimed a single theory or methodology. His genius as a critic was to consider the contributions of Marx, Freud, and feminism-but never to be burdened by their molds-and to carry the understanding gained from looking at contemporary art when considering the ancient. His self-appointed task as art historian was to erode conventionally held notions about the limitations of particular periods in art. Schapiro revealed in the seemingly formulaic dogmatism of early Christian art the vivacious spirit of the individual craftsman. And in the supposed self-absorption and isolation of the expressive modern artist, he exposed engagement with the social world. While deeply involved with the political potential of art, at the core of Schapiro's review is the artist, a human being, with protests, visions, desires, and fears, whose limning of color and form is an act of freedom.

In his fifty years as adviser and trustee of The Jewish Museum, Meyer Schapiro added significant dimension to the museum's mission. At a time when Jews in America were asserting their influence on the art world, Schapiro encouraged the museum to present cutting-edge contemporary art. To expose the reciprocal relationship of old and new, to recognize in ancient ceremonial art the dynamic force of spiritual expressionism, and to read in the avant-garde new utterances of traditional values and ideas: this was the gauntlet that Schapiro threw down in the late 1940s. In its collections and programs, The Jewish Museum continues to embrace the challenge of Meyer Schapiro's dynamic dialectical approach.

In 1983, Neel turned her unflinching eye to a man renowned for his penetrating gaze. Schapiro sits cross-legged with hands folded in his lap, his thin frame filling the armchair. To the pathos of his face Neel adds gray wisps of hair touched with falling light, which suggests a halo of luminescence. His expressive eyes are widened by the raising of his thick brows; the careful delineation of the wrinkles on his forehead proclaims the act of seeing as an act of will. His lips are parted; he is about to speak. The painting is a conversation between an eighty-three-year-old woman and a seventy-nine-year-old man, between two people who had been moved by but had outlived the political ideals of the thirties, between an artist and a critic who, whether looking at a person or a work of art, combined shrewd analysis of the historically conditioned with visionary understanding of the uniquely individual.

Meyer Schapiro was born in Lithuania in 1904 and at the age of three moved to the United States, where he and his family settled in the predominantly Jewish community of Brownsville, Brooklyn. As a professor of art history at Columbia University, Schapiro was mentor to a number of famous artists, historians, and critics. He was a prolific writer, and his boundless interest was variously captured by the ecstatic tensions of a Romanesque portal, Courbet's empathy for the French peasant, the psychological implications of Van Gogh's boots, and Cezanne's apples as sublimated desires. Yet Schapiro never proclaimed a single theory or methodology. His genius as a critic was to consider the contributions of Marx, Freud, and feminism-but never to be burdened by their molds-and to carry the understanding gained from looking at contemporary art when considering the ancient. His self-appointed task as art historian was to erode conventionally held notions about the limitations of particular periods in art. Schapiro revealed in the seemingly formulaic dogmatism of early Christian art the vivacious spirit of the individual craftsman. And in the supposed self-absorption and isolation of the expressive modern artist, he exposed engagement with the social world. While deeply involved with the political potential of art, at the core of Schapiro's review is the artist, a human being, with protests, visions, desires, and fears, whose limning of color and form is an act of freedom.

In his fifty years as adviser and trustee of The Jewish Museum, Meyer Schapiro added significant dimension to the museum's mission. At a time when Jews in America were asserting their influence on the art world, Schapiro encouraged the museum to present cutting-edge contemporary art. To expose the reciprocal relationship of old and new, to recognize in ancient ceremonial art the dynamic force of spiritual expressionism, and to read in the avant-garde new utterances of traditional values and ideas: this was the gauntlet that Schapiro threw down in the late 1940s. In its collections and programs, The Jewish Museum continues to embrace the challenge of Meyer Schapiro's dynamic dialectical approach.

Information may change as a result of ongoing research.