- Artist/Maker:

- Yael Bartana

- Bio:

- Israeli, b. 1970

- Title:

- Entartete Kunst Lebt (Degenerate Art Lives)

- Date:

- 2010

- Medium:

- 16 mm film and sound, film projector, 5 minute, 14 second loop

- Dimensions:

- Dimensions variable

- Credit Line:

- Purchase: Fine Arts Acquisitions Committee Fund

- Accession Number:

- 2012-32

Not On View

Yael Bartana works in film, video, and still photography. Much of her art is directly political, often setting subjects of vital current concern within a historical context or juxtaposing present crises with episodes and references from past ones. Her films are usually short and crisp in presentation, with a heightened dramatic—even epic—quality.

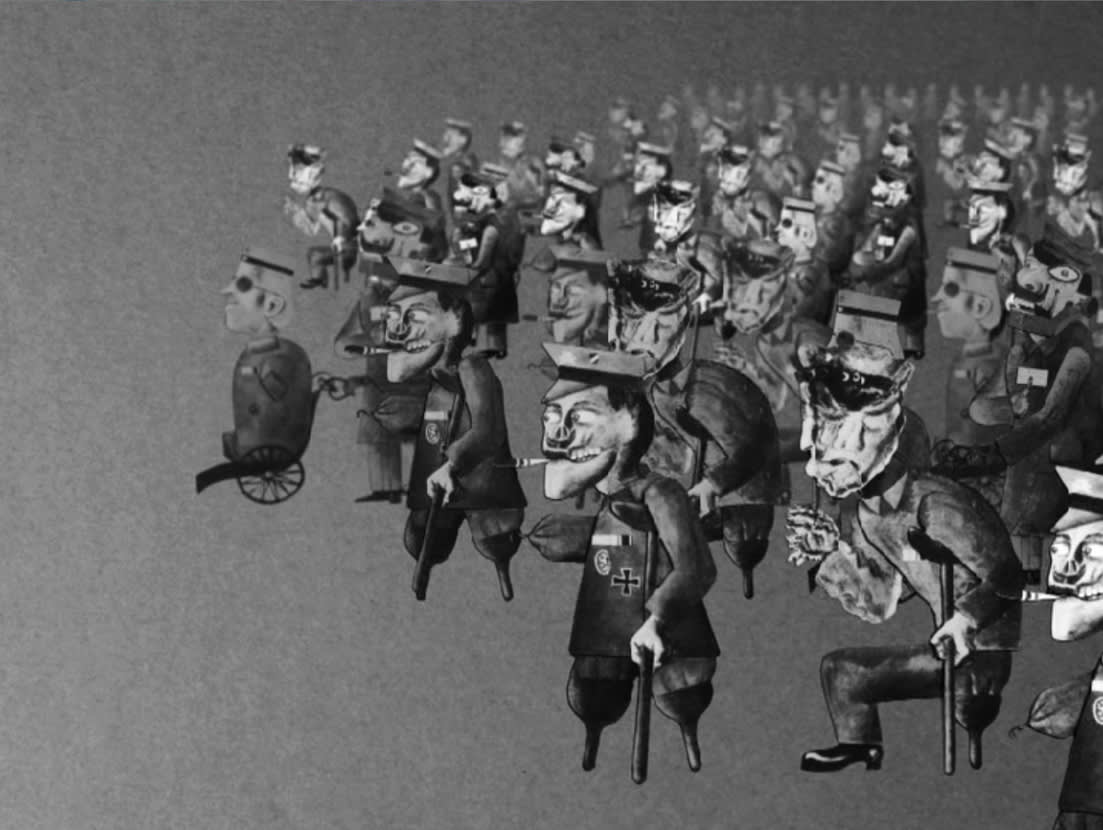

Here, Bartana builds her own statement about war on that of another artist. The German painter and printmaker Otto Dix (1891–1969) was one of the world’s great artists of war imagery. His 1920 painting War Cripples was a scathing indictment of the horrors of war as manifested in the damaged bodies and disturbed minds of combat veterans. His figures are both suffering victims and cartoonish grotesques who participate willingly in a monstrous celebration of national pride.

Under the Nazis Dix’s art was condemned as “degenerate,” a term used by them to describe modernism, which they considered “Jewish” and therefore perverse. War Cripples was exhibited in the infamous Nazi-sponsored 1937 Degenerate Art exhibition and later destroyed.

Bartana employs stop-motion animation to bring Dix’s soldiers to life, repeating the stumbling figures in a vast, purposeless march. She adds the sound of rusty wheelchairs, evoking a painful and labored parade. The lost painting is known only through a black-and-white photograph; in her hands its monochrome evokes utter desolation. In her retelling, Dix’s pitiful veterans form an allegory of twenty-first century war as an unending mass process.

As the film progresses and the army of the wounded grows, the sound of their steps and their false limbs, crutches, and canes comes to resemble that of machine-gun fire. This is echoed in the installation by the noise of the vintage film projector. World War I brought mechanization and technology to warfare; the result was that soldiers suffered catastrophic injury and trauma. Artists were fascinated by this phenomenon, in particular the apparent merging of the human form with the mechanical, such as soldiers who returned with artificial limbs.

The work’s title is multifaceted and steeped in irony. Bartana has reanimated war’s casualties both metaphorically and literally. She reminds us, too, that the Nazi impulse that created an exhibition of supposedly debased art persists. And the title has a third meaning: it is a rebuke to the practice of censoring or dismissing art as corrupt, asserting defiantly that “degenerate” art survives to reveal its unwelcome truths.

Bartana’s macabre military parade is a rejection of the idea of war as a test of courage or expression of national glory. It is a biting, satiric commentary that remains as urgent and contemporary as when Dix first depicted it.

Here, Bartana builds her own statement about war on that of another artist. The German painter and printmaker Otto Dix (1891–1969) was one of the world’s great artists of war imagery. His 1920 painting War Cripples was a scathing indictment of the horrors of war as manifested in the damaged bodies and disturbed minds of combat veterans. His figures are both suffering victims and cartoonish grotesques who participate willingly in a monstrous celebration of national pride.

Under the Nazis Dix’s art was condemned as “degenerate,” a term used by them to describe modernism, which they considered “Jewish” and therefore perverse. War Cripples was exhibited in the infamous Nazi-sponsored 1937 Degenerate Art exhibition and later destroyed.

Bartana employs stop-motion animation to bring Dix’s soldiers to life, repeating the stumbling figures in a vast, purposeless march. She adds the sound of rusty wheelchairs, evoking a painful and labored parade. The lost painting is known only through a black-and-white photograph; in her hands its monochrome evokes utter desolation. In her retelling, Dix’s pitiful veterans form an allegory of twenty-first century war as an unending mass process.

As the film progresses and the army of the wounded grows, the sound of their steps and their false limbs, crutches, and canes comes to resemble that of machine-gun fire. This is echoed in the installation by the noise of the vintage film projector. World War I brought mechanization and technology to warfare; the result was that soldiers suffered catastrophic injury and trauma. Artists were fascinated by this phenomenon, in particular the apparent merging of the human form with the mechanical, such as soldiers who returned with artificial limbs.

The work’s title is multifaceted and steeped in irony. Bartana has reanimated war’s casualties both metaphorically and literally. She reminds us, too, that the Nazi impulse that created an exhibition of supposedly debased art persists. And the title has a third meaning: it is a rebuke to the practice of censoring or dismissing art as corrupt, asserting defiantly that “degenerate” art survives to reveal its unwelcome truths.

Bartana’s macabre military parade is a rejection of the idea of war as a test of courage or expression of national glory. It is a biting, satiric commentary that remains as urgent and contemporary as when Dix first depicted it.

Information may change as a result of ongoing research.