- Artist/Maker:

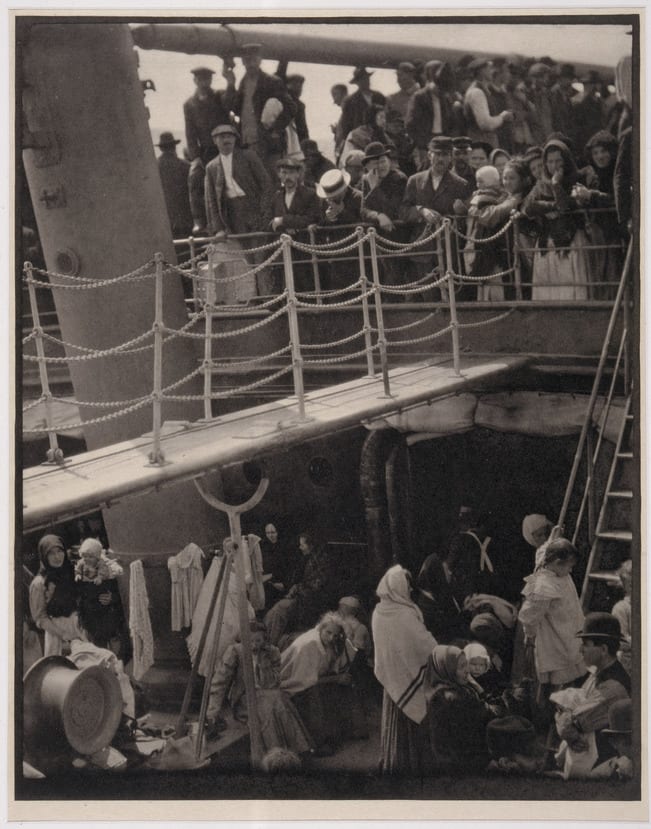

- Alfred Stieglitz

- Bio:

- American, 1864-1946

- Title:

- The Steerage

- Portfolio/Series:

- 291

- Date:

- 1907, printed 1915

- Medium:

- Photogravure

- Dimensions:

- Sheet: 15 7/8 × 11 1/16 in. (40.4 × 28.1 cm) Image: 13 1/4 × 10 1/2 in. (33.7 × 26.7 cm)

- Credit Line:

- Purchase: Mr. and Mrs. George Jaffin Fund

- Accession Number:

- 2000-6

Not On View

In the spring of 1907, the photographer and modern-art impresario Alfred Stieglitz boarded a ship bound for Europe. Leaving from the port of his hometown of Hoboken, New Jersey, he was accompanied by Emmeline, his wife, and their eight-year-old daughter, Katherine. While Stieglitz’s life was comfortably middle-class, Emmeline’s upbringing had been affluent, and she enjoyed luxury. On her account, the Stieglitzes purchased first-class tickets for their week-long passage aboard the Kaiser Wilhelm II, one of the most resplendent ocean liners of the day.

Stieglitz could not stand the stifling bourgeois atmosphere of the first-class quarters. He escaped to the end of his deck, where he found solace in the crowd that appeared before him: men, women, and children confined to the steerage. As the son of German Jewish immigrants, Stieglitz perhaps recognized himself in these weary travelers. He also could not help but notice that the ship’s architecture provided a perfect framework for an unfolding human drama. Using the last of the glass photographic plates that he had on board, Stieglitz created a photograph that has captivated the popular imagination ever since.

Despite its iconic status in the history of art, The Steerage is rarely seen for what it really is: a picture of people leaving, not coming to, America. So strong is its association with the history of immigration that it is hard to separate the impression from reality. Immigration to the United States was then at its peak: over one million steerage passengers are estimated to have arrived in New York in the year this photograph was taken. The third-class travelers depicted may have been successful emigrant workers returning to Europe to visit family and friends, but it is more likely that they were among the thousands who were rejected by immigration officials in the United States for reasons of ill-health, “moral disease,” old age, or excessive poverty.

Modern-day viewers may be quick to interpret this photograph as a critique of the inhumane way immigrants were (and often still are) treated in this country. But although Stieglitz may have identified with his subjects, he was not photographing for a cause. Rather, his main interest was in advancing photography’s potential as fine art. This romanticized view of huddled masses at sea has both formal rigor and emotional pull. Stieglitz considered this photograph his greatest triumph: “If all my photographs were lost, and I’d be represented by just one, The Steerage, I’d be satisfied.”

Although The Steerage is instantly recognizable as a masterpiece today, Stieglitz was not immediately certain that the picture would be a success. He waited four years to publish it, and another two to exhibit it. The Steerage had its gallery debut in 1913, coinciding with the celebrated Armory Show, which introduced avant-garde art to the New York public. Stieglitz purposely performed this “diabolical test,” as he called it, to demonstrate that his photographs could measure up to the latest trends in modern painting. By this time, forward-thinking audiences were able to appreciate the work’s formal innovations: its bisected composition, tight cropping, and the intricate patterns formed by clusters of people. Later, Stieglitz liked to claim that Pablo Picasso had said, “This photographer is working in the same spirit as I am.”

Stieglitz could not stand the stifling bourgeois atmosphere of the first-class quarters. He escaped to the end of his deck, where he found solace in the crowd that appeared before him: men, women, and children confined to the steerage. As the son of German Jewish immigrants, Stieglitz perhaps recognized himself in these weary travelers. He also could not help but notice that the ship’s architecture provided a perfect framework for an unfolding human drama. Using the last of the glass photographic plates that he had on board, Stieglitz created a photograph that has captivated the popular imagination ever since.

Despite its iconic status in the history of art, The Steerage is rarely seen for what it really is: a picture of people leaving, not coming to, America. So strong is its association with the history of immigration that it is hard to separate the impression from reality. Immigration to the United States was then at its peak: over one million steerage passengers are estimated to have arrived in New York in the year this photograph was taken. The third-class travelers depicted may have been successful emigrant workers returning to Europe to visit family and friends, but it is more likely that they were among the thousands who were rejected by immigration officials in the United States for reasons of ill-health, “moral disease,” old age, or excessive poverty.

Modern-day viewers may be quick to interpret this photograph as a critique of the inhumane way immigrants were (and often still are) treated in this country. But although Stieglitz may have identified with his subjects, he was not photographing for a cause. Rather, his main interest was in advancing photography’s potential as fine art. This romanticized view of huddled masses at sea has both formal rigor and emotional pull. Stieglitz considered this photograph his greatest triumph: “If all my photographs were lost, and I’d be represented by just one, The Steerage, I’d be satisfied.”

Although The Steerage is instantly recognizable as a masterpiece today, Stieglitz was not immediately certain that the picture would be a success. He waited four years to publish it, and another two to exhibit it. The Steerage had its gallery debut in 1913, coinciding with the celebrated Armory Show, which introduced avant-garde art to the New York public. Stieglitz purposely performed this “diabolical test,” as he called it, to demonstrate that his photographs could measure up to the latest trends in modern painting. By this time, forward-thinking audiences were able to appreciate the work’s formal innovations: its bisected composition, tight cropping, and the intricate patterns formed by clusters of people. Later, Stieglitz liked to claim that Pablo Picasso had said, “This photographer is working in the same spirit as I am.”

Information may change as a result of ongoing research.