- Object Name:

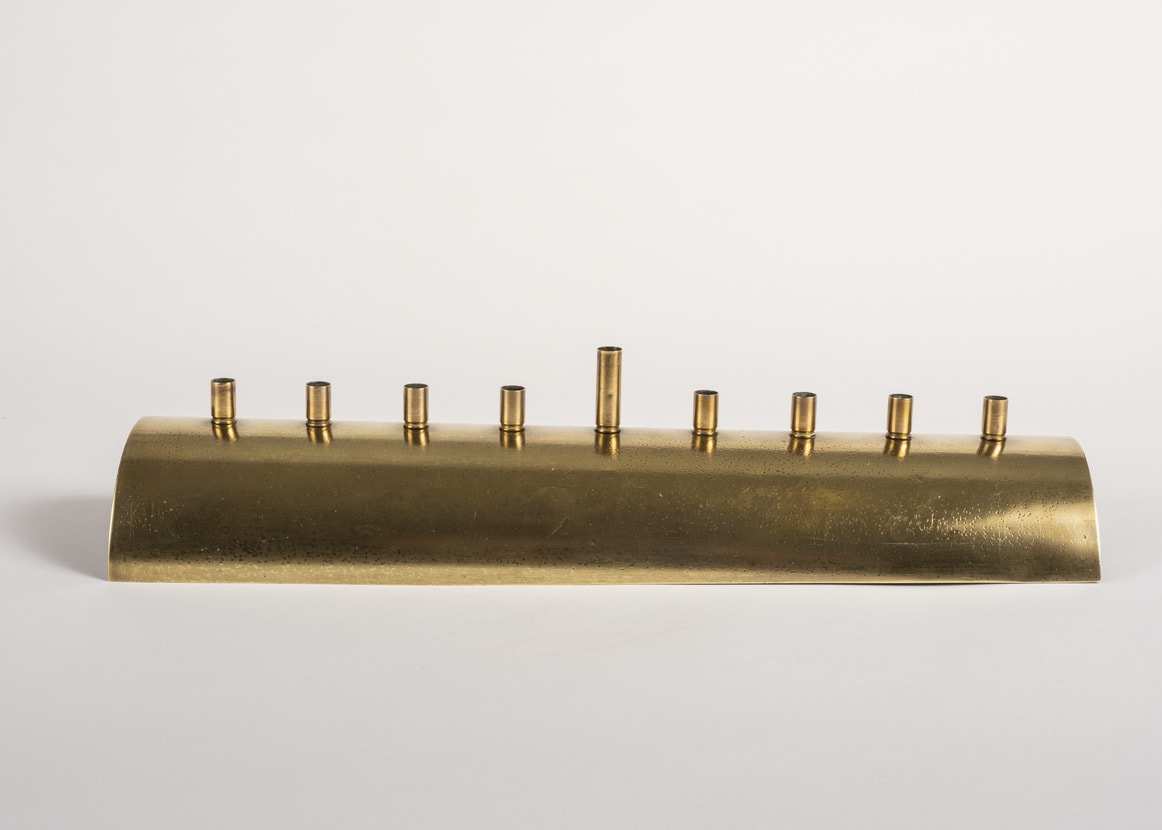

- Hanukkah Lamp

- Designer:

- Donald E. Kooker

- Fabricator:

- Joy B. Steward

- Fabricator:

- Robert J. Creato

- Fabricator:

- Rene A. Vidaurri

- Place Made:

- Republic of Korea, inscriptions added in Japan

- Date:

- 1951

- Medium:

- Copper alloy: cast, chased, and punched

- Dimensions:

- 3 5/8 × 17 3/16 × 4 9/16 in. (9.2 × 43.7 × 11.6 cm)

- Credit Line:

- Gift of Chaplain Meir Engel

- Accession Number:

- JM 59-52

On View

The story of this lamp's creation is a testament to the American principle of freedom of worship and to the spirit of cooperation that can exist between religious groups. The United States Army's X Corps was stationed in Korea in 1951. As Hanukkah approached, Chaplain Meir Engel was unable to locate a lamp so that he could celebrate the festival with the Jewish members of the Corps. Hearing of his dilemma, a fellow officer told Chaplain Engel to contact 1st Lt. Donald E. Kooker of the1st Ordinance Medium Maintenance Company to help solve the problem. Lt. Kooker designed a Hanukkah lamp, which army craftsmen then fabricated out of a shell casing and cartridge shells. A friend of the chaplain then took the lamp to Japan, where the inscriptions were added. Chaplain Engel was indeed able to celebrate Hanukkah that year in Korea, and soon after donated this lamp to The Jewish Museum.

The use of shells and cartridges to fashion various types of objects started to become a common practice in the mid-nineteenth century, when this type of artillery was introduced. Such items have come to be called "trench art" after the trench-style warfare of World War I. The most common metal pieces produced were vases, lighters, letter openers, and finger rings, to name just a few. The contexts for their manufacture were varied. Some items were made by soldiers, either on or near the front, although many were made by blacksmiths or engineers farther in the rear. Soldiers also made trench art in hospitals and prisoner-of-war camps, often for sale. Civilians later picked up the detritus of war from the scrap heaps and fashioned objects for sale to soldiers and to the tourists who soon came to see the battlefield sites. Lastly, commercial firms in Europe and the United States would create objects out of souvenir ordnance brought home by returning soldiers. Many of the items were secular in nature, although crucifixes and pieces with images of the cross were made. Items associated with Judaism appear to be rare.

The use of shells and cartridges to fashion various types of objects started to become a common practice in the mid-nineteenth century, when this type of artillery was introduced. Such items have come to be called "trench art" after the trench-style warfare of World War I. The most common metal pieces produced were vases, lighters, letter openers, and finger rings, to name just a few. The contexts for their manufacture were varied. Some items were made by soldiers, either on or near the front, although many were made by blacksmiths or engineers farther in the rear. Soldiers also made trench art in hospitals and prisoner-of-war camps, often for sale. Civilians later picked up the detritus of war from the scrap heaps and fashioned objects for sale to soldiers and to the tourists who soon came to see the battlefield sites. Lastly, commercial firms in Europe and the United States would create objects out of souvenir ordnance brought home by returning soldiers. Many of the items were secular in nature, although crucifixes and pieces with images of the cross were made. Items associated with Judaism appear to be rare.

Information may change as a result of ongoing research.