- Object Name:

- Wall Hanging

- Artist/Maker:

- Berthold Wolpe

- Bio:

- British, b. Germany, 1905-1989

- Workshop of:

- Rudolf Koch

- Bio:

- German, 1876-1934

- Place Made:

- Offenbach, Germany

- Date:

- 1925

- Medium:

- Linen: embroidered with linen thread

- Dimensions:

- 83 1/2 × 57 1/2 in. (212.1 × 146.1 cm)

- Credit Line:

- Gift of Milton Rubin

- Accession Number:

- JM 33-48

Not On View

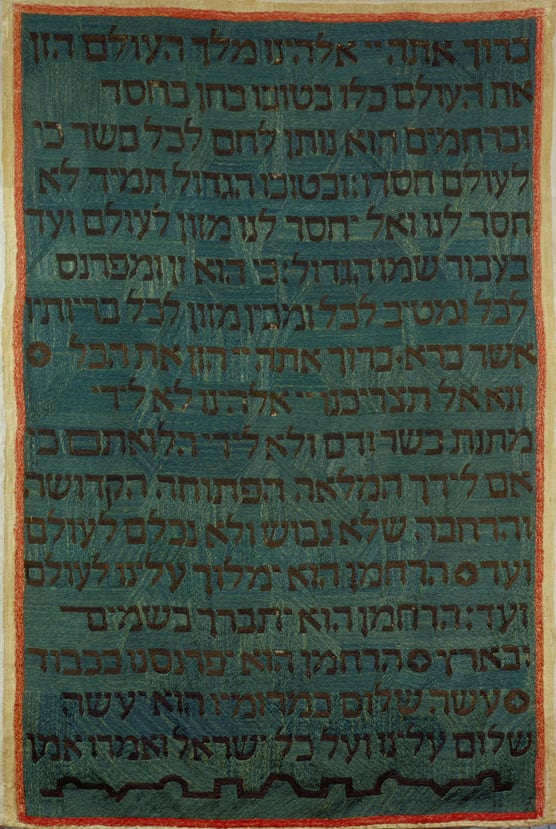

The elegant simplicity of this embroidered hanging was a product of the sophisticated partnership of an imaginative student, a knowledgeable master craftsman, and an enlightened patron: Berthold Wolpe, Rudolf Koch, and Siegfried Guggenheim, respectively. Its aesthetic appeal depends on the expressive design of its Hebrew letters, which inscribe the text of the grace after meals and the superb craftsmanship of the handweaving and embroidery.

Rudolf Koch became known primarily as a fine book designer and creator of new typefaces. His fascination with letters and words and his admiration of the Bible led him to design many Christian texts. Simultaneously, his longtime interest in medieval embroidery encouraged him to study handweaving, spinning, and dyeing. It was through these media that Koch's interest in decorative lettering would reach a new level of sophistication. By 1924, he had set up a textile workshop but had not yet received any commissions. Shortly after, commissions came from his longtime friend Siegfried Guggenheim. These resulted in five religious textiles for the Guggenheim home.

For this work, Koch drew on the skills of his twenty-year-old student and Guggenheim's coreligionist Berthold Wolpe to create a design based on Hebrew letters. Wolpe clearly was influenced in his modernization of Hebrew letters by his master's ideas about the stylization and simplification of Renaissance Latin typefaces. He also incorporated Koch's theory about the word as an almost self-sufficient means of decoration. The simplicity of this textile design and its reliance on traditional techniques also relate to the contemporaneous development of textile workshops of the early Bauhaus. Wolpe, who immigrated to England in 1935, is now famed for the excellence of his own typefaces and the more than 1,500 books and jackets designed for the firm Faber & Faber. His respect for the past led to creative adaptations of traditional techniques and designs. Wolpe acknowledged the influence of Koch, whose style had its origins in the Jugendstil, the German version of Art Nouveau, and in the numerous Arts and Crafts movements that spread across Germany in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries.

The symbiotic relationship of this creative trio led to further developments. It was Guggenheim's Jewish textile commissions that again encouraged Koch to produce a series of seven large tapestries based on both the Hebrew and Christian Bibles. These were intended as church decorations. At the same time, Wolpe produced another Jewish ceremonial work in a different medium for the Guggenheim dining room. Wolpe's copper ewer and basin of 1926 carry the Hebrew benediction for the ritual washing of hands before meals. Guggenheim could thus begin and end his meals using finely wrought contemporary works in the observance of traditional Jewish practice.

The triumvirate's efforts culminated with the Offenbach Passover Haggadah of 1927, published and edited by Guggenheim himself. The book used one of Koch's innovative Latin type designs for the German translation opposite Wolpe's Hebrew lettering of the original text. Woodcut illustrations by another member of the workshop, Fritz Kredel, further enriched the Haggadah. For Koch, the collaborative nature of the publication of this communal text added to its fundamental value.

Rudolf Koch became known primarily as a fine book designer and creator of new typefaces. His fascination with letters and words and his admiration of the Bible led him to design many Christian texts. Simultaneously, his longtime interest in medieval embroidery encouraged him to study handweaving, spinning, and dyeing. It was through these media that Koch's interest in decorative lettering would reach a new level of sophistication. By 1924, he had set up a textile workshop but had not yet received any commissions. Shortly after, commissions came from his longtime friend Siegfried Guggenheim. These resulted in five religious textiles for the Guggenheim home.

For this work, Koch drew on the skills of his twenty-year-old student and Guggenheim's coreligionist Berthold Wolpe to create a design based on Hebrew letters. Wolpe clearly was influenced in his modernization of Hebrew letters by his master's ideas about the stylization and simplification of Renaissance Latin typefaces. He also incorporated Koch's theory about the word as an almost self-sufficient means of decoration. The simplicity of this textile design and its reliance on traditional techniques also relate to the contemporaneous development of textile workshops of the early Bauhaus. Wolpe, who immigrated to England in 1935, is now famed for the excellence of his own typefaces and the more than 1,500 books and jackets designed for the firm Faber & Faber. His respect for the past led to creative adaptations of traditional techniques and designs. Wolpe acknowledged the influence of Koch, whose style had its origins in the Jugendstil, the German version of Art Nouveau, and in the numerous Arts and Crafts movements that spread across Germany in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries.

The symbiotic relationship of this creative trio led to further developments. It was Guggenheim's Jewish textile commissions that again encouraged Koch to produce a series of seven large tapestries based on both the Hebrew and Christian Bibles. These were intended as church decorations. At the same time, Wolpe produced another Jewish ceremonial work in a different medium for the Guggenheim dining room. Wolpe's copper ewer and basin of 1926 carry the Hebrew benediction for the ritual washing of hands before meals. Guggenheim could thus begin and end his meals using finely wrought contemporary works in the observance of traditional Jewish practice.

The triumvirate's efforts culminated with the Offenbach Passover Haggadah of 1927, published and edited by Guggenheim himself. The book used one of Koch's innovative Latin type designs for the German translation opposite Wolpe's Hebrew lettering of the original text. Woodcut illustrations by another member of the workshop, Fritz Kredel, further enriched the Haggadah. For Koch, the collaborative nature of the publication of this communal text added to its fundamental value.

Information may change as a result of ongoing research.