- Artist/Maker:

- George Segal

- Bio:

- American, 1924-2000

- Title:

- The Holocaust

- Date:

- 1982

- Medium:

- Plaster, wood, and wire

- Dimensions:

- Dimensions variable

- Credit Line:

- Purchase: Gift of Dorot Foundation

- Accession Number:

- 1985-176a-l

- Copyright:

- Art © The George and Helen Segal Foundation/Licensed by _VAGA_, New York, NY

Not On View

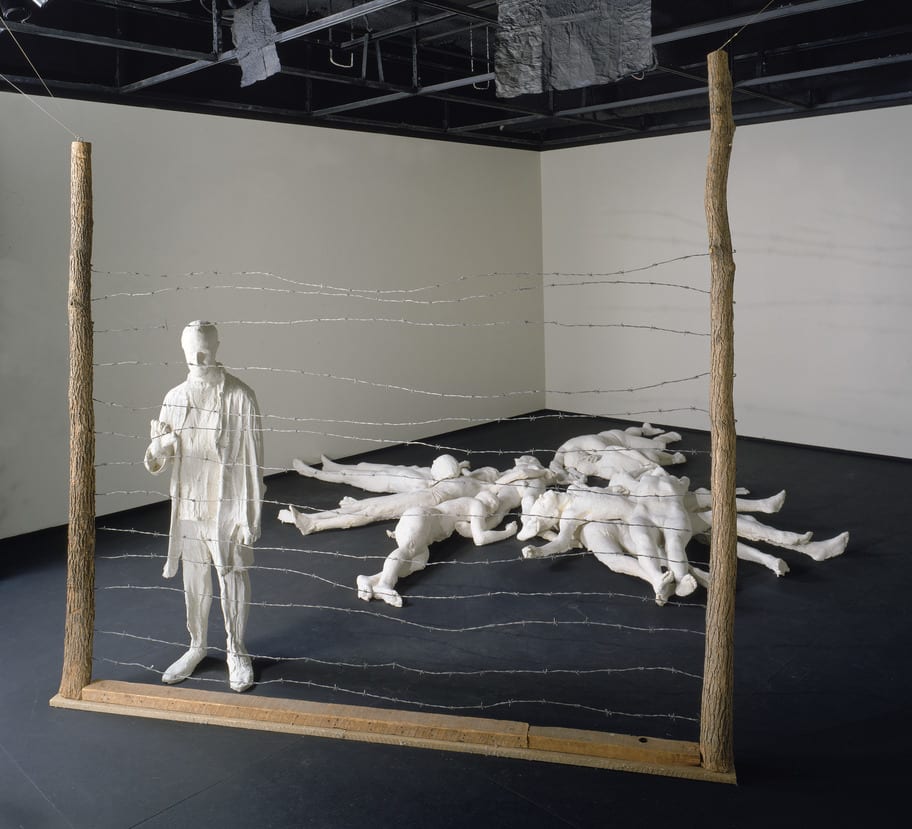

Monuments to the Holocaust and art that memorializes its victims have of necessity been approached with caution in the over seventy years since those tragic events. Questions about whether this subject should be conceived abstractly or realistically have vied with the quandary about whether it is even fitting to attempt a tangible monument to these victims. Many of these works have proved provocative; others have been hotly debated. When it was first installed, George Segal's The Holocaust sparked impassioned discussions over what some called its hyperrealistic representation of Holocaust victims. However, the work-despite its unusual combination of visual challenge and emotional pathos-has quickly evolved into an icon.

Determined to establish such a memorial, the city of San Francisco organized a competition for the commission in 1981. Segal was asked to submit an entry, and he used his hallmark technique of casting living persons directly in plaster for the original model. His proposal was selected as the winning entry and was installed in 1984. Cast in bronze with white patination, it is now prominently sited in Lincoln Park, near San Francisco's Palace of Legion of Honor. The original plaster models constitute the work in The Jewish Museum's collection.

In his haunting representational manner, creating plaster casts of actual individuals and using real props, Segal has condensed many of the horrific images of the devastation into one. A pile of corpses lies behind an actual barbed-wire fence; the figure of a solitary survivor stands mute in the foreground, clutching the sharp metal. As sources, Segal used infamous images taken shortly after the Allied liberation of the camps by such venerable photographers as Margaret Bourke-White and Lee Miller. Similar photographs of disordered mounds of cadavers had already served Picasso for his well-known painting The Charnel House (1944-45). Segal reacted strongly to the obscene disarray of bodies that he was forced to confront in these visual documents. He was shocked by the notorious disregard for the usual sacred rituals of death.

As noted by Sam Hunter, Segal purposely organized the composition to neutralize chaos and inject human meaning into this sculptural transposition from journalistic photography. The indistinct modeling of the ten bodies and the presence of a lone survivor relieve the harrowing reality, permitting the viewer enough remove to engage in Segal's tragic poetry.

The ordered composition functions on a number of levels relating to artistic and literary sources, to Segal's personal iconography, and to his earlier works. The stack of corpses is a realization of Segal's earlier concept for the FDR Memorial (which opened in Washington, D.C., in 1997), the discomforting motif that he had also considered for The Execution of 1967. The star-shaped arrangement of the bodies in The Holocaust includes the figure of a woman holding a half-eaten apple, an allusion to Eve; a figure with outstretched arms, symbolic of Jesus and suffering; and an older man lying near a young boy, referring to Segal's earlier, controversial Abraham and Isaac (1978), which he originally created to memorialize the students killed at Kent State University in Vietnam War protests in 1970. The man poised by the fence is based on a Bourke-White photograph and was modeled from a friend of Segal's, an Israeli survivor of the camps. This living presence emphasizes hope and survival. The figure's physical isolation and psychic pain-exaggerated by an unconscious clutching at the sharp edge of the actual barbed wire-are perhaps best described in words of another survivor and eloquent witness of these atrocities, Elie Wiesel: "How can one repress the memory of indifference one had felt toward the corpses? Will you ever know what it is like to wake up under a frozen sky, on a journey toward the unknown, and record without surprise that the man in front of you is dead, as is the one before him and the one behind you? Suddenly a thought crosses one's mind; What if I too am already dead and do not know it?"

Determined to establish such a memorial, the city of San Francisco organized a competition for the commission in 1981. Segal was asked to submit an entry, and he used his hallmark technique of casting living persons directly in plaster for the original model. His proposal was selected as the winning entry and was installed in 1984. Cast in bronze with white patination, it is now prominently sited in Lincoln Park, near San Francisco's Palace of Legion of Honor. The original plaster models constitute the work in The Jewish Museum's collection.

In his haunting representational manner, creating plaster casts of actual individuals and using real props, Segal has condensed many of the horrific images of the devastation into one. A pile of corpses lies behind an actual barbed-wire fence; the figure of a solitary survivor stands mute in the foreground, clutching the sharp metal. As sources, Segal used infamous images taken shortly after the Allied liberation of the camps by such venerable photographers as Margaret Bourke-White and Lee Miller. Similar photographs of disordered mounds of cadavers had already served Picasso for his well-known painting The Charnel House (1944-45). Segal reacted strongly to the obscene disarray of bodies that he was forced to confront in these visual documents. He was shocked by the notorious disregard for the usual sacred rituals of death.

As noted by Sam Hunter, Segal purposely organized the composition to neutralize chaos and inject human meaning into this sculptural transposition from journalistic photography. The indistinct modeling of the ten bodies and the presence of a lone survivor relieve the harrowing reality, permitting the viewer enough remove to engage in Segal's tragic poetry.

The ordered composition functions on a number of levels relating to artistic and literary sources, to Segal's personal iconography, and to his earlier works. The stack of corpses is a realization of Segal's earlier concept for the FDR Memorial (which opened in Washington, D.C., in 1997), the discomforting motif that he had also considered for The Execution of 1967. The star-shaped arrangement of the bodies in The Holocaust includes the figure of a woman holding a half-eaten apple, an allusion to Eve; a figure with outstretched arms, symbolic of Jesus and suffering; and an older man lying near a young boy, referring to Segal's earlier, controversial Abraham and Isaac (1978), which he originally created to memorialize the students killed at Kent State University in Vietnam War protests in 1970. The man poised by the fence is based on a Bourke-White photograph and was modeled from a friend of Segal's, an Israeli survivor of the camps. This living presence emphasizes hope and survival. The figure's physical isolation and psychic pain-exaggerated by an unconscious clutching at the sharp edge of the actual barbed wire-are perhaps best described in words of another survivor and eloquent witness of these atrocities, Elie Wiesel: "How can one repress the memory of indifference one had felt toward the corpses? Will you ever know what it is like to wake up under a frozen sky, on a journey toward the unknown, and record without surprise that the man in front of you is dead, as is the one before him and the one behind you? Suddenly a thought crosses one's mind; What if I too am already dead and do not know it?"

Information may change as a result of ongoing research.